-

IN PRAISE OF IMPERMANENCE

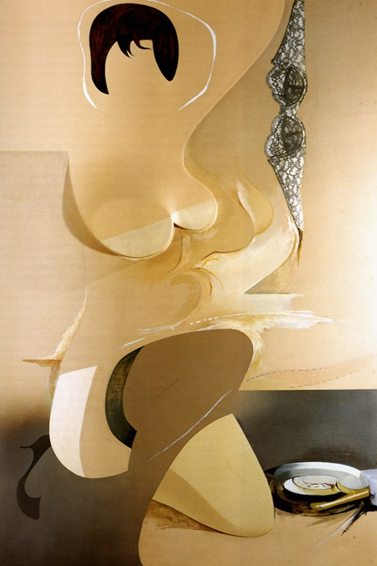

In searching for a way to register how the consumer culture of post-war Great Britain differed from that of the other English-speaking victor, British artist Richard Hamilton decided to incorporate plastics into the art that he created—the thought being that the synthetic materials would reflect the increasingly synthetic life of Americans. Enter “Pin-up” a mixed composition of a molded plastic breastplate and paint, all adhered to a plywood background.¹ Hamilton glued his part and painted it, unaware of the effect that those solvents might have on a thermoset material. To his audience in Great Britain, whose food rationing had ended just a year before, the work was revolutionary and quite fetching. He sought to contrast the young, glamorous, American household of plenty that he found in American publications and movies with a home country whose splintered-wood and wicker-wire fences still cordoned-off bombed out buildings in various stages of reconstruction. But he conveyed more than he imagined, for when he moved his masterpiece it cracked right across the breastplate and delaminated from the plywood backing. Hamilton had no idea that solvents, temperature variation, UV light, humidity, and movement might lead to environmental stress-cracking. As it turned out, he built worse than he knew, for the materials that he chose to illustrate the ephemeral nature of modern life were as transitory as the fashions that he sought to depict.

And just in case someone might miss it, he displayed on his disjointed model a single nylon stocking, a product that unmistakably telegraphed the sensual nature of modern American life. In so choosing he harkened back a quarter century, to the time that DuPont introduced polyamides. In 1929 Charles Stine wrangled a quarter million dollars out of management’s budget and used that money to fund his “Pure Science Division.” Now able to hire talented academicians, he brought on-board Wallace Carothers whose research focused on polyamides, and by 1936 they had managed to produce not just nylon, but nylon fibers as well. As it turned out, most silk fibers were sourced in Japan, and given that country’s increasing alienation during the 1930s, the thought that the silk-stocking industry might be an attractive market led Carothers’s team to start looking for ways to spin their new material. Three years and thousands of dollars later they had managed to develop the machinery and production processes that enabled them to manufacture stockings. But not any stocking—what we now call hosiery. Displayed first at the San Francisco International Exposition and the New York World’s Fair in 1938, nylons created a such a stir that when they finally went on sale in October 1939 the first 4,000 pairs sold out in three hours. The war interrupted the supply, but by 1945, when the product again become available, DuPont projected sales of 360 million pairs annually.² Clearly Hamilton was on to something, but what was it about nylons that is so interlinked in our imagination that we instantly recognize that black stocking?

To begin, consumers usually disassociate the product from the material—nylons were attractive to consumers not so much to because they were synthetic, but because they served as a social construct.³ In an age of rising hem lines they provided legitimacy by covering the legs, however sheer that cover might be, while also smoothing and casing over any imperfections otherwise visible. But that explanation begs the question, why were those same consumers so concerned about legitimacy or covering up imperfections? The suggestion that comes to mind has to do with an emergent property of human behavior, namely, fashion. We love novelty and choose something new, simply because it is new, over something that is older but still functional, even if the new item does not work as well as the old one. It’s hard to beat wool’s insulative properties, but from the time it became a fashion statement (the “preppy look” of the 1920s then associated with sports) to now it has largely been supplanted by synthetics. The ski apparel most of us use today have zero wool, for example. That is not to say that we do not use wool, we do, but its role is now more of a fashion accessory, not as a functional item of clothing. All of which is a long way of saying that the Devi’s Dictionary is correct — fashion is that despot whom the wise ridicule, then obey.

Footnotes:

¹ Roksana Filipowska, “Richard Hamilton’s Plastic Problem,”

Science History Magazine

(October 15, 2016), online at, https://www.sciencehistory.org/stories/magazine/richard-hamiltons-plastic-problem

² Hillary S. Kativa, “Synthetic Threads,” Science History Magazine, (October, 2016), https://www.sciencehistory.org/stories/magazine/synthetic-threads

³ Maria Elvira Callapez, Sara Marques da Cruz, Marta Martins Neto, „Plastics Hand in Hand with Consumers—A Route in Portugal,” ICON: Journal of the International Committee for the History of Technology, 24 (2018-2019): 108-126.

CONTACT US TO LEARN MORE: 704-602-4100