704-602-4100 | FAX: 704-602-4114 | University Research Park, 8900 Research Drive Charlotte, NC 28262 | Mon-Fri: 8:00AM-4:30PM

Thoughts gathered from the Polymers Center, by Philip S. Shoemaker

“In reflecting on them, every one must be struck with astonishment; for the same reasoning power which tells us that most parts and organs are exquisitely adapted for certain purposes, tells us with equal plainness that these rudimentary or atrophied organs are imperfect and useless.”

-Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species, 1859

In May 1848, Henry Bewley, of the Gutta Percha Company of London, patented a process for making flexible syringes and tubes of gutta percha. He described the process as one that involved “filling a suitable mold with a substance in a granular state,” after which he would “subject these molds to a heat sufficient to liquefy the gutta percha, which on subsequent cooling will be found to retain the exact shape or figure of the molds.”

A (Very) Quick History of Injection Molds

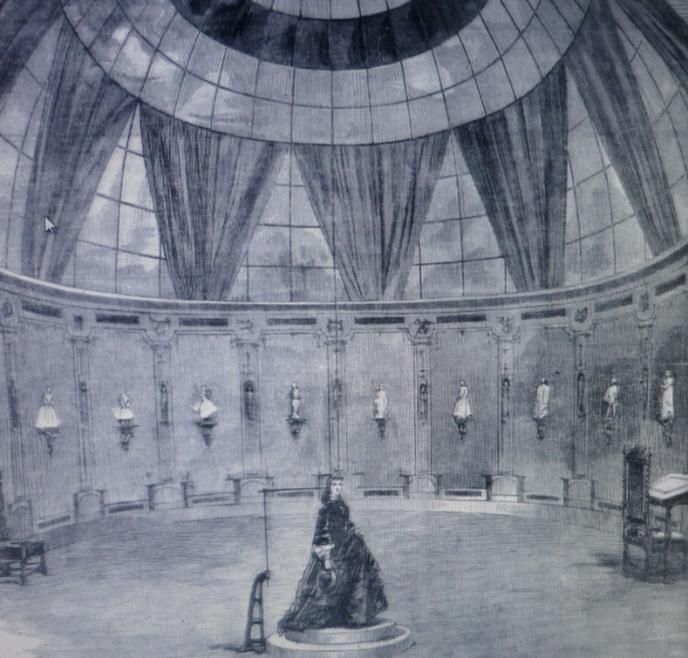

One might think that 3D printing started with Chuck Hall’s patent for stereolithography in 1986, but the roots of antecedent inventions extend remarkably deep into the past, starting with a French sculptor, François Willème. Sometime in the mid-1850s, while he was attending art school in Paris and making models for manufacturers of art bronzes, Willème learned of photography and realized its potential as an aid for making silhouettes.

From Sculpting to Printing—Technical Dead-Ends of the 3D Revolution

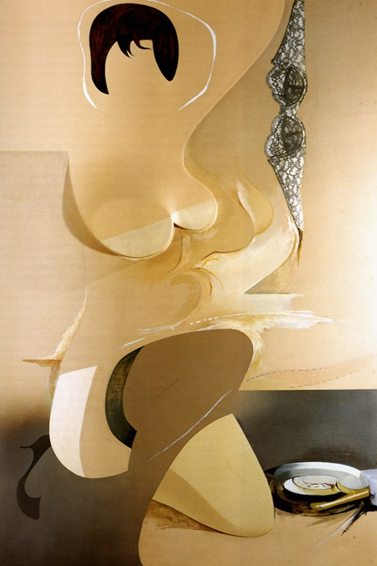

In searching for a way to register how the consumer culture of post-war Great Britain differed from that of the other English-speaking victor, British artist Richard Hamilton decided to incorporate plastics into the art that he created—the thought being that the synthetic materials would reflect the increasingly synthetic life of Americans. Enter “Pin-up” a mixed composition of a molded plastic breastplate and paint, all adhered to a plywood background.

In Praise of Impermanence

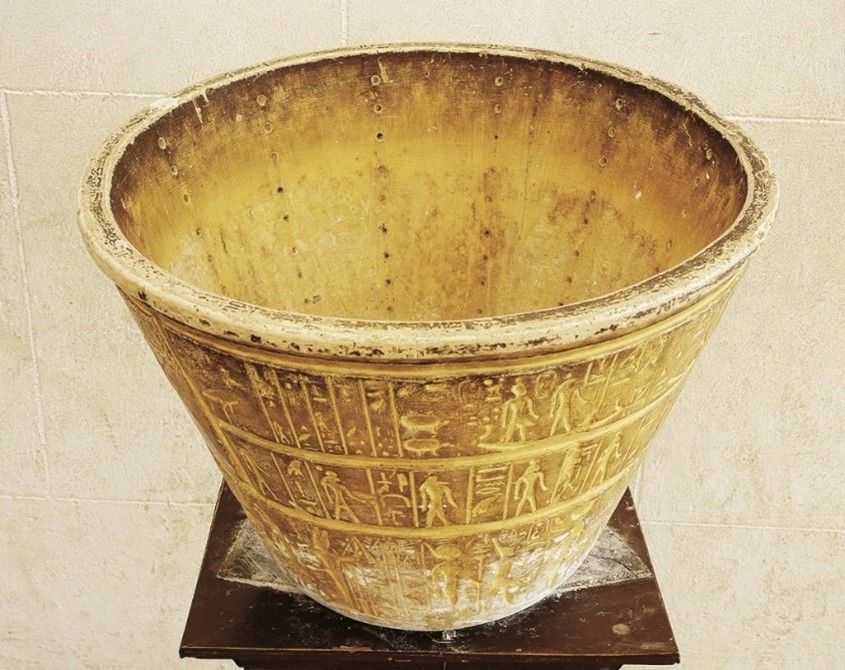

We think of mistletoe in terms of Christmas celebrations, but for centuries it was associated with an adhesive thread derived from its berries, called viscin, proving that even parasites may provide some measure of utility. [1] To the ancients, viscin was related to viscosus, which referred to anything sticky and was also related to that which melts or flows, especially a malodorous or foul fluid. [2] That, of course raises questions of fluid flow.

Newton And The Water Clock

We now live among synthetics—so much so that we hardly notice them. But that was not always so, nor was the term plastic always endowed with the same meaning that it has today. Originally it meant sculpting, such as, “Painting, Carving and Plasticke are all but one and the same arte.”

Synthetic Vision And Synthetic Reality

Contact Us

Have a question? Call Today!

University Research Park

8900 Research Drive

Charlotte, NC 28262

Let Us Know

Copyright 1998 - 2022 | Polymers Center | All Rights Reserved